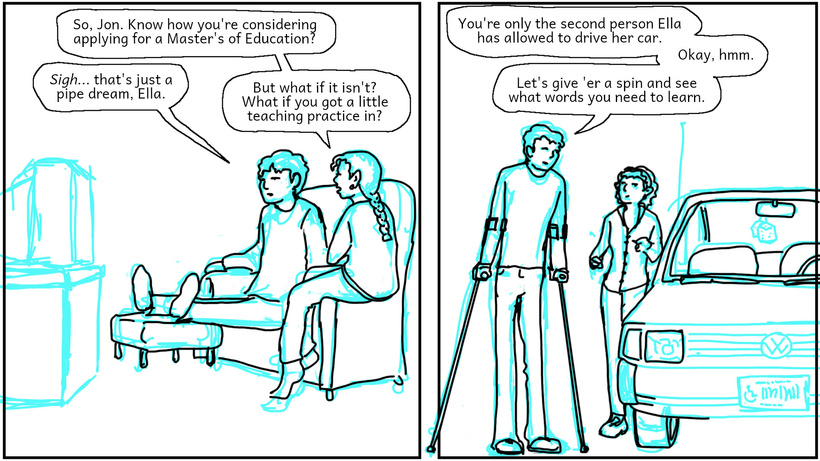

Alien Romance, the daily comic strip

Jon is sitting on the couch, watching TV. I should've drawn his crutches in there. I keep intending to go back into panels and draw either his crutches or wheelchair, whichever is appropriate, while he's sitting on the couch. Ella comes to bother him.

"So, Jon," she says. "Know how you're considering applying for a Master's of Education?"

Jon sighs. "That's just a pipe dream, Ella."

"But what if it isn't?" insists Ella. "What if you got a little teaching practice in?"

Now Jon is standing on the sidewalk beside Ella's VW Rabbit. Cathy is awkwardly holding the keys. "You're only the second person Ella has allowed to drive her car," Jon observes. "Okay, hmm. Let's give 'er a spin and see what words you need to learn."

***

Jon's friendship with Cathy is a whole story arc unto itself. He's a very verbal communication oriented person, although he's not particularly talkative himself. He just insists on things being stated clearly, and resents confusion. Cathy, meanwhile, is a whirlwind of chaos. Sort of. She's only as chaotic as I am - internally consistent, but not up to the clarity standards of the people around her. So how do these two connect?

It might be that Jon perceives Cathy as a challenge, and one he takes very seriously. Can he find common ground with his good friend's new wife, even if they can't properly converse?

Also, talking to her is like talking to a dog; she's warmly attentive but can't understand very much of what he says. The perfect confidant! Maybe?

And what does Cathy see in Jon? Maybe she sees nonthreatening masculinity. In the book, Cathy has run-ins a couple of times with men that end up going badly for her, to the point where she actually tells Maurice that she's afraid to try again. (In French, and it goes right over his head.)

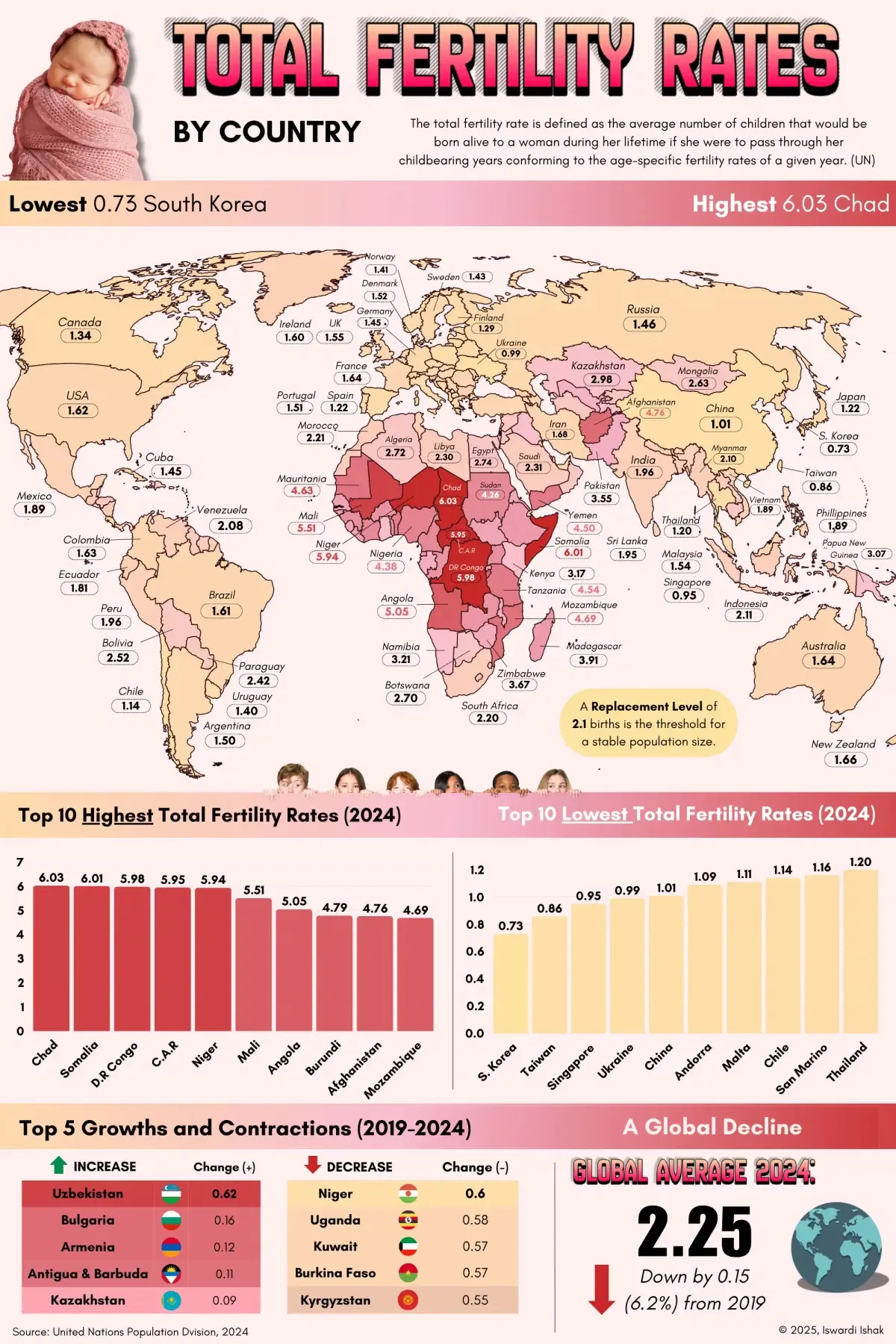

Total fertility rate is defined as the average number of children that would be born alive to a woman during her lifetime if she were to pass through her childbearing years conforming to the age-specific fertility rates of a given year.

Total fertility rate is defined as the average number of children that would be born alive to a woman during her lifetime if she were to pass through her childbearing years conforming to the age-specific fertility rates of a given year. Chad

Chad Somalia

Somalia DR Congo

DR Congo Central African Republic

Central African Republic Niger

Niger Mali

Mali Angola

Angola Burundi

Burundi Afghanistan

Afghanistan Mozambique

Mozambique Mauritania

Mauritania Mayotte

Mayotte Tanzania

Tanzania Yemen

Yemen Benin

Benin Nigeria

Nigeria Sudan

Sudan Cameroon

Cameroon Côte d’Ivoire

Côte d’Ivoire Uganda

Uganda Guinea

Guinea Togo

Togo Equatorial Guinea

Equatorial Guinea Burkina Faso

Burkina Faso Republic of the Congo

Republic of the Congo Zambia

Zambia Madagascar

Madagascar Ethiopia

Ethiopia Gambia

Gambia Liberia

Liberia Comoros

Comoros Samoa

Samoa South Sudan

South Sudan Senegal

Senegal Guinea-Bissau

Guinea-Bissau Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone Eritrea

Eritrea Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe Rwanda

Rwanda São Tomé & Príncipe

São Tomé & Príncipe Gabon

Gabon Malawi

Malawi Vanuatu

Vanuatu Pakistan

Pakistan Solomon Islands

Solomon Islands Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan Ghana

Ghana French Guiana

French Guiana Nauru

Nauru Palestine

Palestine Iraq

Iraq Namibia

Namibia Tuvalu

Tuvalu Kenya

Kenya Kiribati

Kiribati Tonga

Tonga Papua New Guinea

Papua New Guinea Tajikistan

Tajikistan Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan Marshall Islands

Marshall Islands Micronesia

Micronesia Israel

Israel Kyrgyzstan

Kyrgyzstan Guam

Guam Egypt

Egypt Algeria

Algeria Eswatini

Eswatini Botswana

Botswana Syria

Syria Lesotho

Lesotho Turkmenistan

Turkmenistan Mongolia

Mongolia Timor-Leste

Timor-Leste Haiti

Haiti Djibouti

Djibouti Jordan

Jordan Cambodia

Cambodia Bolivia

Bolivia Oman

Oman Honduras

Honduras Paraguay

Paraguay Laos

Laos Guyana

Guyana Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia Libya

Libya Guatemala

Guatemala Fiji

Fiji American Samoa

American Samoa Suriname

Suriname Lebanon

Lebanon Faroe Islands

Faroe Islands Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua South Africa

South Africa Western Sahara

Western Sahara Réunion

Réunion Bangladesh

Bangladesh Indonesia

Indonesia Seychelles

Seychelles Panama

Panama Monaco

Monaco Myanmar

Myanmar U.S. Virgin Islands

U.S. Virgin Islands Venezuela

Venezuela Belize

Belize Peru

Peru India

India Nepal

Nepal Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka Greenland

Greenland Vietnam

Vietnam Philippines

Philippines Mexico

Mexico Palau

Palau Tunisia

Tunisia Ecuador

Ecuador Bahrain

Bahrain Georgia

Georgia Montenegro

Montenegro North Korea

North Korea El Salvador

El Salvador Bulgaria

Bulgaria Brunei

Brunei Moldova

Moldova Qatar

Qatar Armenia

Armenia Romania

Romania Barbados

Barbados Iran

Iran New Zealand

New Zealand Australia

Australia France

France Colombia

Colombia United States

United States Turkey

Turkey Brazil

Brazil Ireland

Ireland Slovenia

Slovenia Slovakia

Slovakia Maldives

Maldives United Kingdom

United Kingdom Malaysia

Malaysia Liechtenstein

Liechtenstein Trinidad & Tobago

Trinidad & Tobago Denmark

Denmark Kuwait

Kuwait Portugal

Portugal Argentina

Argentina Serbia

Serbia Bosnia & Herzegovina

Bosnia & Herzegovina Hungary

Hungary Croatia

Croatia North Macedonia

North Macedonia Russia

Russia Czechia

Czechia Bhutan

Bhutan Germany

Germany Cuba

Cuba Switzerland

Switzerland Netherlands

Netherlands Sweden

Sweden Norway

Norway Luxembourg

Luxembourg Uruguay

Uruguay Belgium

Belgium Cyprus

Cyprus Estonia

Estonia Jamaica

Jamaica Canada

Canada Latvia

Latvia Albania

Albania Greece

Greece Austria

Austria Costa Rica

Costa Rica Poland

Poland Finland

Finland Mauritius

Mauritius Spain

Spain Belarus

Belarus Japan

Japan United Arab Emirates

United Arab Emirates Lithuania

Lithuania Italy

Italy Thailand

Thailand San Marino

San Marino Chile

Chile Malta

Malta Andorra

Andorra China

China Ukraine

Ukraine Singapore

Singapore Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico Taiwan

Taiwan South Korea

South Korea Hong Kong (SAR)

Hong Kong (SAR) Macau (SAR)

Macau (SAR) Global Average

Global Average